Published in guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 26 July 2011 11.56 BST

written by Sean O'Hagan

It's 40 years since the troubled US photographer took her own life, but her images continue to reveal the camera's predatory nature

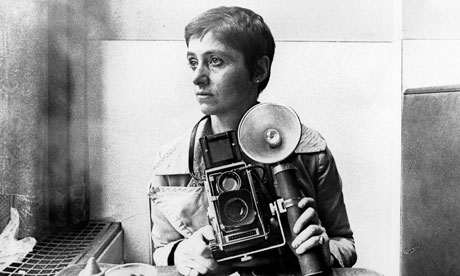

Camera obscura ... Diane Arbus poses for a portrait in New York c 1968 Photograph: Roz Kelly/Getty Images

Diane Arbus killed herself, aged 48, on 26 July 1971. On the 40th anniversary of her death, it's worth reconsidering her artistic legacy. Her work remains problematic for many viewers because she transgressed the traditional boundaries of portraiture, making pictures of circus and sideshow "freaks", many of whom she formed lasting friendships with.

If Arbus undoubtedly felt at home among the outsiders she photographed, she also experienced a frisson of guilty pleasure when photographing them. "There's some thrill in going to a sideshow," she once confessed of her nocturnal visits to the circus tents of Coney Island, where performers were still earning a living in the 1960s. "I felt a mixture of shame and awe."

Her works make us question not just her motives for looking at what the critic Susan Sontag – with typical hauteur – called "people who are pathetic, pitiable, as well as repulsive", but also our own. In perhaps the most angry essay in her book On Photography, Sontag insists that Arbus's gaze is "based on distance, on privilege, on a feeling that what the viewer is asked to look at is really other".

The "other" is not what it used to be. We live in a time when it is ubiquitous, whether in voyeuristic TV shows about "embarrassing bodies" or documentaries about sexual exhibitionists or conjoined twins. Nevertheless, Arbus's black-and-white portraits – particularly of those with mental disabilities or physical abnormalities – retain their power to unsettle and disturb. Here, whatever her intention, the cruel often seems to outweigh the tender. What's more, her portraits always send us back to Arbus: to her need to not just photograph but befriend her subjects; her seemingly insatiable fascination with the unusual; her often fragile state of mind. (She killed herself for reasons that remain mysterious.)

Later this year a new biography, entitled Diane Arbus: An Emergency in Slow Motion, will be published. The author is William Todd Schultz, a professor of psychology at Pacific University, who specialises in what he calls "psychobiography". Once again, as with Patricia Bosworth's celebrated book about the photographer, it is the life – and mind – of the artist that is being probed in an attempt to shed some light on the photographs. For his research, Schultz spoke at length to Arbus's therapist. This, I would hazard, did not go down well with the famously controlling Arbus estate who, as Schultz put it recently, "seem to have this idea, which I disagree with, that any attempt to interpret the art diminishes the art".

Yet with Arbus, as with Nan Goldin, the life and the art are inextricably intertwined. Of late though, Arbus's identification with her subjects has been interpreted not, as Sontag insists, as a kind of prurient voyeurism, but as a way of understanding the world and shedding new light on its fringes. "To cast Arbus in the role of a tragic figure who identified with 'freaks' is to trivialise her accomplishment," Sandra S Philips, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco, told the Smithsonian magazine in 2004. "She was a great humanist photographer who was at the forefront of a new kind of photographic art."

I would agree with the latter half of that sentence while disagreeing with the former. Arbus, as the great American critic and curator John Szarkowski recognised when he first showed her work in his New Documents group exhibition at Moma in New York in 1967, was certainly a trailblazer of a new photographic aesthetic, by turns raw and unflinching, disturbing and illuminating. But a humanist? Only if your view of humanity is essentially pessimistic and tinged with neurotic narcissism.

Arbus may have felt an enormous empathy with the people she photographed, but she was not one of them, however much she identified with their outsider status. She had her own troubles, but they were of a different order. The work she left behind remains powerful not just because of its dark formal beauty or its stark vision, but because it asks questions of the viewer about the limits of looking, about the vicariousness and predatory nature of photography, and about our complicity in all of this.

When we look at an Arbus photograph, we cannot help feeling that we are intruders or voyeurs, even though her subjects are tied to a time and place that has all but vanished. A sense of complicity – hers and ours – lies at the very heart of her power. Her images hold us in their sway even when our better instincts tell us to look away. Perhaps her greatest gift is that she understood that conflict instinctively, and did more than anyone to exploit it artistically.

Now see this

In 2002 and 2003, photographer Ken Griffiths travelled extensively in what is known as Welsh Patagonia. In doing so, he was following in the footsteps of Welsh pioneers who journeyed into the interior of Patagonia as far as the Andes, which border Chile. His photographic record includes landscapes, cityscapes and portraits, all of which attest to the beautiful otherness of the region, and a selection is showing at London's Michael Hoppen Gallery until 20 August.

• Sean O'Hagan is the 2011 winner of the Royal Photographic Society's J Dudley Johnston award. The award recognises achievement in the field of photographic criticism

written by Sean O'Hagan

It's 40 years since the troubled US photographer took her own life, but her images continue to reveal the camera's predatory nature

Camera obscura ... Diane Arbus poses for a portrait in New York c 1968 Photograph: Roz Kelly/Getty Images

Diane Arbus killed herself, aged 48, on 26 July 1971. On the 40th anniversary of her death, it's worth reconsidering her artistic legacy. Her work remains problematic for many viewers because she transgressed the traditional boundaries of portraiture, making pictures of circus and sideshow "freaks", many of whom she formed lasting friendships with.

If Arbus undoubtedly felt at home among the outsiders she photographed, she also experienced a frisson of guilty pleasure when photographing them. "There's some thrill in going to a sideshow," she once confessed of her nocturnal visits to the circus tents of Coney Island, where performers were still earning a living in the 1960s. "I felt a mixture of shame and awe."

Her works make us question not just her motives for looking at what the critic Susan Sontag – with typical hauteur – called "people who are pathetic, pitiable, as well as repulsive", but also our own. In perhaps the most angry essay in her book On Photography, Sontag insists that Arbus's gaze is "based on distance, on privilege, on a feeling that what the viewer is asked to look at is really other".

The "other" is not what it used to be. We live in a time when it is ubiquitous, whether in voyeuristic TV shows about "embarrassing bodies" or documentaries about sexual exhibitionists or conjoined twins. Nevertheless, Arbus's black-and-white portraits – particularly of those with mental disabilities or physical abnormalities – retain their power to unsettle and disturb. Here, whatever her intention, the cruel often seems to outweigh the tender. What's more, her portraits always send us back to Arbus: to her need to not just photograph but befriend her subjects; her seemingly insatiable fascination with the unusual; her often fragile state of mind. (She killed herself for reasons that remain mysterious.)

Later this year a new biography, entitled Diane Arbus: An Emergency in Slow Motion, will be published. The author is William Todd Schultz, a professor of psychology at Pacific University, who specialises in what he calls "psychobiography". Once again, as with Patricia Bosworth's celebrated book about the photographer, it is the life – and mind – of the artist that is being probed in an attempt to shed some light on the photographs. For his research, Schultz spoke at length to Arbus's therapist. This, I would hazard, did not go down well with the famously controlling Arbus estate who, as Schultz put it recently, "seem to have this idea, which I disagree with, that any attempt to interpret the art diminishes the art".

Yet with Arbus, as with Nan Goldin, the life and the art are inextricably intertwined. Of late though, Arbus's identification with her subjects has been interpreted not, as Sontag insists, as a kind of prurient voyeurism, but as a way of understanding the world and shedding new light on its fringes. "To cast Arbus in the role of a tragic figure who identified with 'freaks' is to trivialise her accomplishment," Sandra S Philips, curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco, told the Smithsonian magazine in 2004. "She was a great humanist photographer who was at the forefront of a new kind of photographic art."

I would agree with the latter half of that sentence while disagreeing with the former. Arbus, as the great American critic and curator John Szarkowski recognised when he first showed her work in his New Documents group exhibition at Moma in New York in 1967, was certainly a trailblazer of a new photographic aesthetic, by turns raw and unflinching, disturbing and illuminating. But a humanist? Only if your view of humanity is essentially pessimistic and tinged with neurotic narcissism.

Arbus may have felt an enormous empathy with the people she photographed, but she was not one of them, however much she identified with their outsider status. She had her own troubles, but they were of a different order. The work she left behind remains powerful not just because of its dark formal beauty or its stark vision, but because it asks questions of the viewer about the limits of looking, about the vicariousness and predatory nature of photography, and about our complicity in all of this.

When we look at an Arbus photograph, we cannot help feeling that we are intruders or voyeurs, even though her subjects are tied to a time and place that has all but vanished. A sense of complicity – hers and ours – lies at the very heart of her power. Her images hold us in their sway even when our better instincts tell us to look away. Perhaps her greatest gift is that she understood that conflict instinctively, and did more than anyone to exploit it artistically.

Now see this

In 2002 and 2003, photographer Ken Griffiths travelled extensively in what is known as Welsh Patagonia. In doing so, he was following in the footsteps of Welsh pioneers who journeyed into the interior of Patagonia as far as the Andes, which border Chile. His photographic record includes landscapes, cityscapes and portraits, all of which attest to the beautiful otherness of the region, and a selection is showing at London's Michael Hoppen Gallery until 20 August.

• Sean O'Hagan is the 2011 winner of the Royal Photographic Society's J Dudley Johnston award. The award recognises achievement in the field of photographic criticism